Current

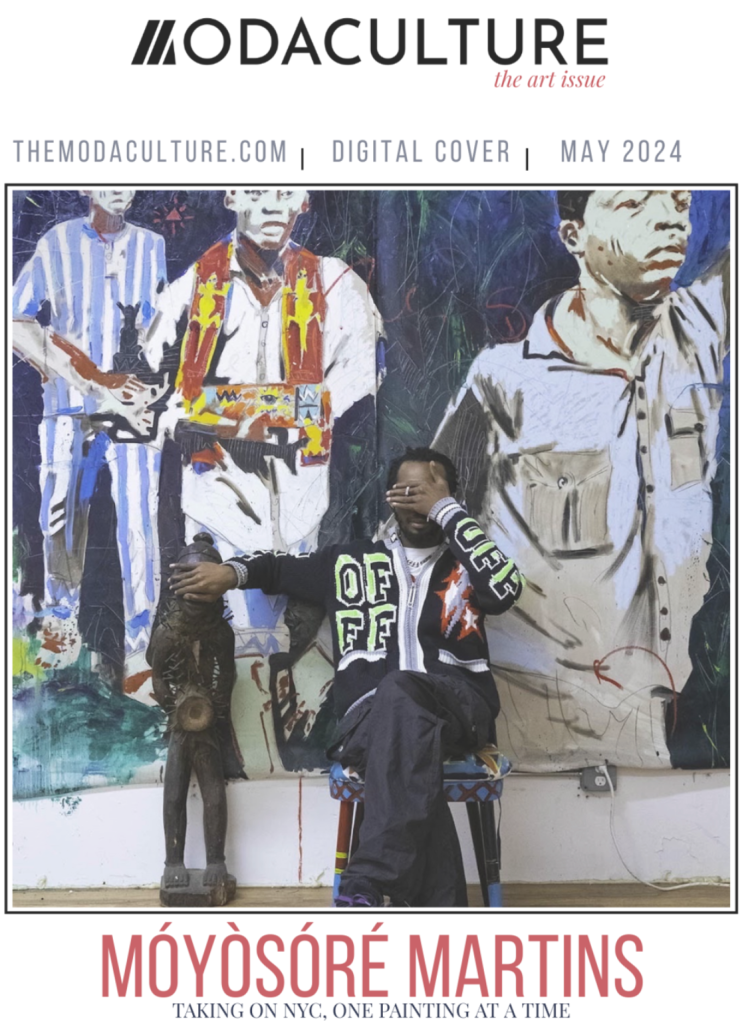

MOYOSORE MARTINS

Móyòsóré Martins: Taking on NYC, One Painting at a Time

By Gertrude Oby April 30, 2024

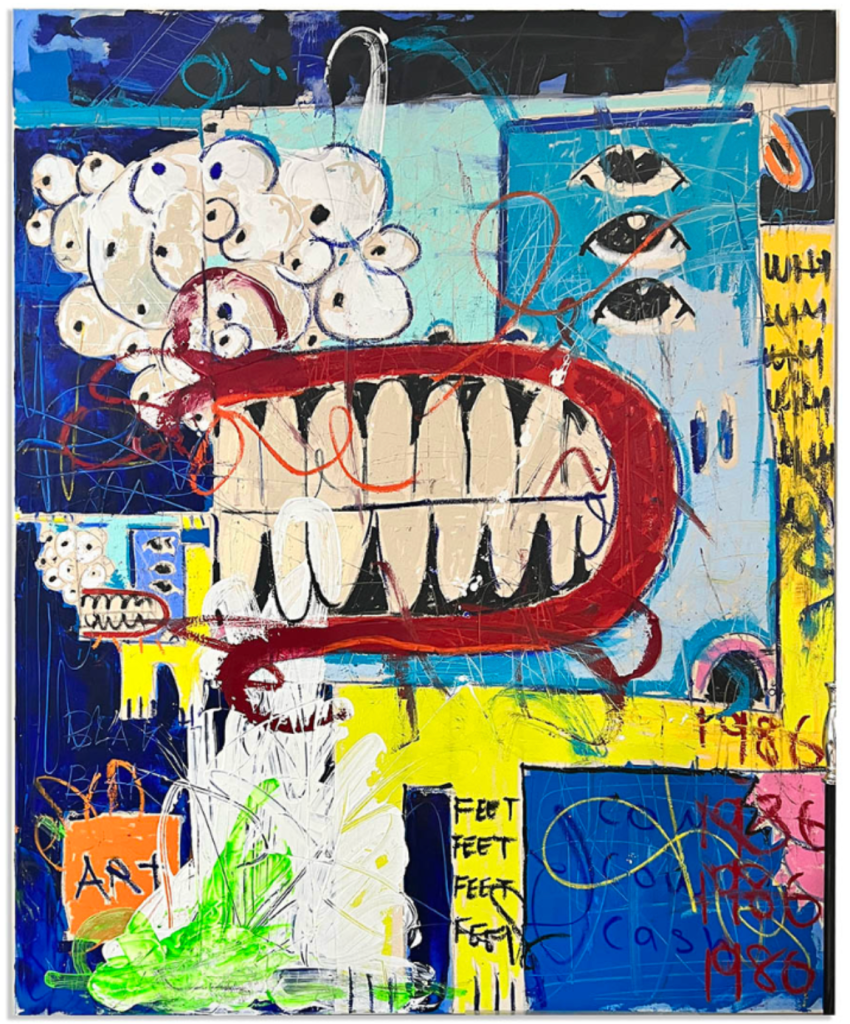

My artwork is intentionally raw and I like to use a lot of different materials and have rough-cut edges on the canvas. The paintings are textured with scratches, scribbles, and mud-like paint, as well as clay, liquid plastic, oil sticks, and chunky layers of oil paint. I layer the background and then deconstruct them, which gives the feeling of wear and tear on the canvas. No painting is alike as each has symbolic patterns and encrypted messages hidden within it. I want to merge the vision with the given and the new world that I live in now. The word “Why?” is seen in a lot of the work because it leaves you asking the same question.

—MÓYÒSÓRÉ MARTINS

Attestation (Vouch), 2022 is a vibrant and energetic piece that showcases the artist’s unique blend of figurative, abstract, and narrative elements. The title is the artist claiming his spot, evidence of his work and style, and awareness of his position in the art world. This is his first auction. The painting features a central totemic figure with exaggerated features, bold brushstrokes, and raw energy.

He is one of today’s most collected emerging, contemporary African artists; his contemporary works have become in high demand among the art community of collectors, auctioned at Sotheby’s and Phillips in New York. In this conversation with Gertrude Oby for Modaculture‘s May cover, Móyòsóré Martins chats about his artistic journey, dealing with his emotions, and the lifestyle choices he’s made to get him to where he is today.

It’s been over a week since that interview with Martins and still, I’m swayed by the intensity of that one-hour-plus Zoom studio session. This intensity which I speak of must come as no surprise to many, I mean it is an artist we speak of. But it wasn’t that, it was the realization that no matter how many artists you have shared space with in conversation, you never quite get used to that deep feeling of being sucked into their world which almost often felt like a mosaic of buried emotions begging to make their way to the surface. With each artist comes a different range of emotions, a different kind of organized chaos. Of thoughts. Of life lessons. Of experiences. The good, the bad, and the ugly. It was the same with Móyòsóré Martins. And he didn’t hold back while telling his story.

The visual artist, now one of the most collected in New York City, did not start out as a success. It took a lot for him and from him to get there; from dealing with parents who didn’t support his work, leaving behind the place he called home to migrate to the United States in 2015, to working menial jobs to make ends meet while waiting for his dream life as an artist to kick off or not. He grew up in Lagos city as the last child of his parents. He did live a rebellious little life in his younger days—kicked out of school twice—and eventually moved to Ghana to give university education a try again. And now that he is here, it doesn’t get into his head. When asked about his success, he quickly, almost awkwardly, responds briefly before changing the subject.

“Success comes in different forms. Success, to me as an artist, is being free from all the norms which is something I embrace. I could wake up on a Monday, when everybody is going to work, and decide to go shopping or like, just chill with the TV and relax. That’s success—being able to give back, and change people’s lives, in America as well as back home, that’s what success is to me not really the sales. I mean the sales, that’s amazing. It does give you the approval and the freedom and the means to have a good studio, materials and a good body of team. I would sound crazy if I said that doesn’t really count, it’s a blessing, and I don’t take it for granted. I’ll just move past that because I really don’t like talking about money and success and all those things.”

Móyòsóré Martins. Photographed by Daniella Liguori © 2024

But away from all that success, art remains selfish, according to him. It is jealous and wants all of him. You could tell from his journey. He tells us that it has been a stormy ride, a dark one at that, because it’s all a game of perception and an endless cycle of sowing and reaping, and one has to stick it out, like it or not. “What you put in is what you get, you know. How you see yourself is how people see you. It’s just about you gaining mastery of your craft and living it. It’s not something you wake up today and go like ‘I wanna be an artist today, and then tomorrow you make some money and then the next, you wanna be something else. You don’t even choose yourself, you need to be chosen for things like this. It’s deeper, it could be frustrating, it could be depressing, it could be very dark. It’s art. It drags you in, it’s selfish. It’s very jealous.”

Does he have shortcomings and regrets when it comes to his art? Not at all. He embraces everything that comes with it and stays vulnerable through it all as he has had to sacrifice everything for it. So, the bigger question becomes this: How much of all these experiences goes into his art? “I’m an abstract expressionist, I try to move away from my realism or anything that a camera can do. So that is number one. You just have to give everything in,” he says.

The dry days are longer than the wet but the wet days feel better. The wet days cover for the drought but the dry days are very long. That’s why I say you need to be chosen for this because we’re not all built to be crazy. It is only a crazy person who believes in something that’s not even happening yet. Just like religion, we believe in something we don’t see, some feel it and some can’t even feel it.

MÓYÒSÓRÉ MARTINS, MODACULTURE MAY 2024

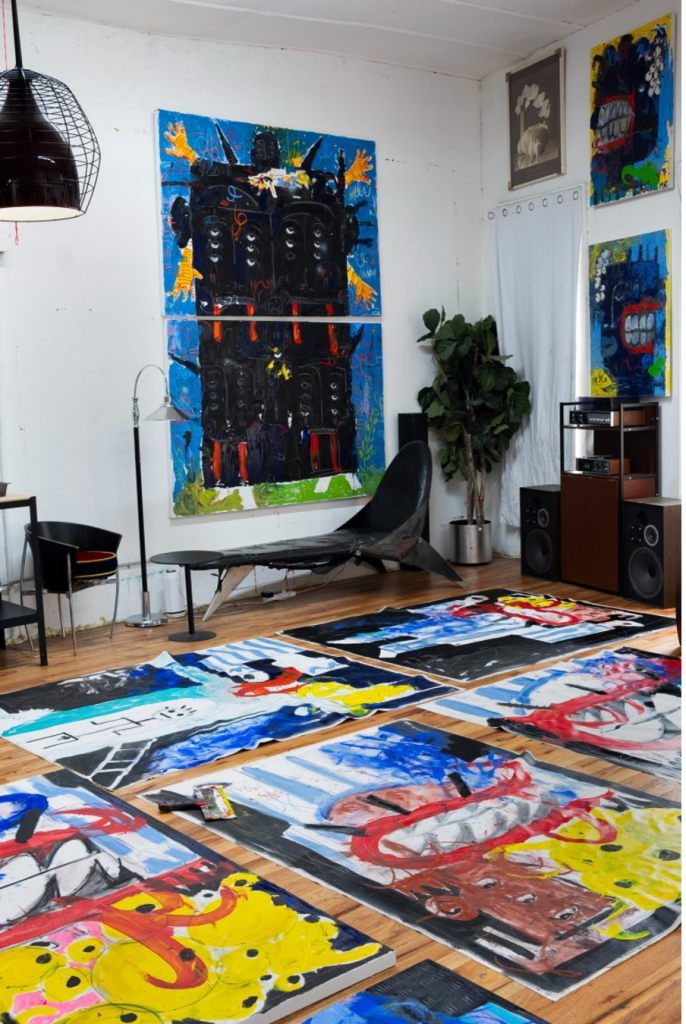

“So, people that don’t feel it, they believe in those things even though they don’t feel it yet and growing up being catholic, an alter boy, everything all catholic schools and stuff and now I’m spiritual, I believe in everything but mainly I believe in spirituality, intuition, my consciousness and I believe in myself so I engrave and infuse everything into my work. There is no way out, that’s my therapy. That’s my canvas, that’s the way I get to say things I can’t say to normal human beings without appearing crazy.” As we talk, he walks me through his over 3,000 square feet studio featuring two large rooms, one he works in and one for relaxation, as well as a storage room and roof deck, in the heart of New York and it was quite the experience. It was full of art pieces, floor to ceiling, all over. It was a world of its own, Martins’s not-so-little world. In it, you’ll find pieces; art in progress, art completed, bare canvas, and layers of tools that bring all of his ideas and thoughts to life. It consumes—his relationship with art—but he makes it work, devoting hours, days, and weeks to seeing nobody else but his art. It’s what saved him and got him off the street, anyway.

Móyòsóré Martins photographed in his Bronx, NY studio room. Photographed by Daniella Liguori © 2024

“That’s what saved me. That’s what got me off the street. That’s what changed my name. That is what gave me the life I have so I owe everything to it. You can’t cheat the energy. The people collecting art, because I don’t say they buy art, it’s ‘collection.’ You could buy clothes and stuff but when you start getting rare things, it is a collection. The people that collect art, they know what they feel, they know what to expect, they’re not fools. They work hard for everything they have and everything they own and for them to want to collect anything you create, they need to feel the frequency. It’s all about energy, vibrations and everything. It’s more than just putting a canvas, or a paint and a brush on a canvas and be like ‘Errr, okay that’s it.’ Nah!”

Everything goes into his art. It’s all in there. It’s his life. It’s his one medium of expression. Whatever he could give is right there in his art, whether all of him or some of him, it’s all there.

“Sometimes I get 50-50, I put everything in there, sometimes it’s 70-30, it’s in there. Sometimes it’s like 90-10, it’s in there. Sometimes a piece is extremely borderline dark, and twisted, but it’s in there, you could feel what I go through at that moment,” but it’s not always dark and twisted and sad because “sometimes you see the paintings full of joyful manifestations,” and you could tell, “it’s in there.”

If art is a spectrum, then you can be certain this painter takes himself through the stretch.

“The reason I create like that,” he continues, “is because I don’t like being in front of the cameras, I don’t see myself as this influencer with a camera with my phone and all those things, I’ve never been about that, I’ve always been about my business because I’m very obsessed with this stuff. There’s something I see that I know is gonna happen but not yet, I’m on the way there. As much as I keep seeing these things, there’s no way for me to stop. That’s why I do this every day, trying to learn every day. I work every day just as if I haven’t sold anything yet. I’m hungry as hell, not desperate but extremely articulated and intentional with everything with my moves. It’s a lifestyle to it—what you eat, what you wear, where you go, it all boils down to what you create—the kind of books you read, what you watch on TV, the people you talk to, your access as human beings, you know. So the designs in general, the architecture, music, sound, design, the food, smell, you know we can’t just be one-sided; an artist is just an umbrella of that creative-know-all so everything is all in there.

If I’m going through my emotions and everything, you could feel it in the pieces. I won’t lie or hide what I create because most of the time I don’t put the messages in myself, it comes. Sometimes I get the premonitions and sometimes I don’t”.

MÓYÒSÓRÉ MARTINS, MODACULTURE MAY 2024

So, what’s the takeaway from Móyòsóré Martins’s art? The constant message is that life is an eventful journey that gets dark, every now and then, and art is a gift that gets one through. As much as one may have heard this, it could never stop being true—one ought to seek the light continuously. This constant struggle is not unique to him, many other artists like him experience it too. For instance, there’s always that pendulum that swings back and forth from cash cow status to doing art just for what it is. For some artists, that pendulum is just a phase; for others, it’s their whole life. “I talk to many artists, from time to time, and understand that they are trying to get clarity of the light because we’re all in a tunnel, some will never find the light. Some will just get a crack of the light and some are in the light and refuse to shine the light and let other people have a trail of where they’re going.”

“So most of us have always been about the journey—life itself, where we’re all heading, what we’re going through and what is to be expected of us and what to expect from people being an artist, being a cash cow, because it starts with a hobby, then it turns into a business, then it turns into something else and how to stay grounded in everything because most people that went to art school they never taught them about how to handle success and how to handle the art market, human relations, aesthetic, your voice, signature and everything. They just think that after going to art school, that’s it. Nah! It’s way deeper, finding your voice is a lifetime kind of thing so people are chosen and blessed to have it. That’s why I said it’s a gift. It could be anybody else as well. With that basic understanding of how the universe actually works, I input everything in my work trying to make it as self-explanatory as possible so I don’t have to be at the shows or in front of the cameras.”

But, in essence, what was this journey truly like and how did it all begin? From the time Móyòsóré Martins first arrived in New York until he was discovered and started selling his art, he amassed even more experiences making his discovery quite the story. None of it was pretty. He walked into many galleries in the city and got too many rejections so he stopped seeking representation. But he never stopped making art. He painted so many pieces and hung them in his home, there wasn’t a single white space left. There were pieces unhung in every room in his apartment. Eventually, he bent a knee to capitalism. While at his security job, he landed a freelance role as a graphic artist where he worked and made a few cheques. He’d assumed he could make a living off those cheques at the security job working two shifts in a 24-hour schedule. It was cold.

Móyòsóré Martins in his Bronx, NY studio, 2023 Photography by Daniella Liguori © 2024

“But I’ve been used to the nos ever since I was a kid anyway so it doesn’t mean anything to me anymore since the people that actually gave birth to me have been telling me that all my life so who are you to tell me ‘No’ that’s gonna matter? So that’s what really made me very stubborn. I’ve changed now, I’m very calm and laid back. So I would go around Chelsea, Soho, all these places looking for gallery representatives, then they’d tell me ‘No’ and then I stopped going around. I was just working. I was just painting and keeping my paintings. Yeah, I have my paintings in my beautiful apartment. You need to love what you do, it’s like a tailor who makes clothes and doesn’t even wear what you make, it makes no sense. So my paintings were beautifully curated in my apartment alongside So my paintings were beautifully curated in my apartment alongside other things I’ve collected because I’m a collector myself. Then I worked for many years being an independent artist. I was bored, and I needed to do something else you know in NY, everybody is very fast and swift and I was just in my studio. I would look out of my studio and see people go to work and come back and I was doing quite okay but I felt like I was missing out, it felt like a stimulation in New York. I was like ‘Dude you need to be out there again,’ so I started putting out CVs.”

Foreseeing, 2023 Oil, oil stick, pigments, graphite on canvas 75 X 70 inches.

While narrating this, he doesn’t miss out on any chance to acknowledge and appreciate his support system, emphasising that he did not get to where he is today alone. When he met his best friend, now wife Joanna Martins, they worked hard to build each other and work their way to the top. “I had no one, then I met my best friend, Joanna, who is my wife. We became very close friends and everything. She saw my vision and what I wanted to do. We actually helped build ourselves together. It wasn’t as if I was walking around with a cape on my back like Superman. I had a support system, people who saw things I wouldn’t see. I just want to put that out there.”

He touches on the subject of identity and how much impact it could have on the trajectory of one’s life. “Being Black in America is real, there’s an advantage to it, there’s also a disadvantage to it, you will see the advantage if you think differently. I’ve been different. I don’t follow man-made rules or anything. Your idea of me is not the reality of who I am, so I’ve always been like that. I walk into any room. I’ve never seen colours like that. You know I’m married to a white woman, my kids are mixed so I’ve never seen anything like colour. I’m very stubborn if I want something I’m walking in there. And I’m not from here so that’s a very major advantage, it makes you see things differently, and it makes you work out of the box entirely because I came as a grown man with a culture already so having culture is an advantage to who you are as a person, you know the convenience, the language, the food is an essence of your individuality so I had that, so I knew who I was, I knew where I come from, so there’s a difference and the Black people here as well they see that and they go through that as well. It’s a lot. It’s mental stuff, things that make people think small of themselves, it’s traumatising.”

Lekki 2021, Oil on Canvas 73 x 64 inches (About #EndSARs and the 2020 Lekki Toll Gate Massacre in Lagos, Nigeria).

There are more bright sides to being a POC which are advantageous to one’s life as an artist, and he delves into that.

Yes, my tradition, how I grew up and me being Black—being Black is different—it comes with so many things. It comes with history. It comes with wisdom. It comes with patience. It comes with the ability of self-consciousness and all these things make you a good artist. You just have the natural intuition that what you’re doing is the right thing as much as the whole world says ‘Nah, that ain’t it.’ So, it’s a blessing, I wouldn’t change it for anything.

MÓYÒSÓRÉ MARTINS, MODACULTURE MAY 2024

“And growing up back home, with everything I went through and saw, I feel like that’s what made me who I am today—my ability to push things through.”

All it takes is one moment.

At this point, we circle back to the topic of his discovery. Móyòsóré Martins tells me that his boss and her husband had gone on a voyage to Switzerland, and somehow they had stumbled on his painting. Surprisingly, he had worked with them awhile and had kept his artistry safely tucked away from them. He would sit in on meetings while they discussed major artists, museums, etc., and he never pitched himself or leveraged an opportunity to project himself, as most people would have. He sat in on those meetings, simply taking notes—being an assistant—and then, he would go home to his art. “Hi Móyò,” he narrates his boss’ email, “Don’t tell me this is your work, so you’ve been an artist and you never told me”, followed by a promise to pay a visit to his studio as soon as they both returned. They’d insisted on taking a tour of wherever he made his art. After they explored his space and the pieces, they signed him on and they’ve worked together ever since at Traffic Arts.

A section of Móyòsóré Martins’s studio.

Móyòsóré Martins is not your typical artist who’d go with the ebbs and flows of inspiration. Routines and structure were everything to him. He was so dedicated he had several pieces to churn out each month. Whether the inspiration came or not, he would sit with his bare canvas staring it in the face till it succumbed to him. “I paint at midnight. I paint from 12 am to 6/7 am and then wake up and it’s a circle. I don’t have a normal life, I was woken up for this interview. I don’t have a normal life. You can’t be normal if you want to do something different because you can’t fight the originality, you’re gonna be fake, you’re gonna be something else.”

I live in my art world in the sense that I don’t do anything else but art. I don’t engage in anything that does not revolve around this, I don’t go to clubs, I don’t go to parties, I don’t go anywhere. Sometimes, I’ll be in my studio for two weeks without seeing the sun. It’s a routine. It’s a practice. It’s a possession. You need to be possessed with this stuff. I’m being honest with you and whoever is in your life needs to understand that you didn’t choose this, you were chosen for this.

MÓYÒSÓRÉ MARTINS, MOD

Móyòsóré Martins photographed in his Bronx, NY studio room

His creative process is pretty sensual. From preparing his canvas to enjoying some jazz, smoking a bit and then drinking some coffee in between, it’s got a certain pizazz to it. “I prep my canvas, I leave it on the wall, I walk around, I enjoy myself, I put some jazz music on, I drink, I smoke a little bit, I drink coffee, I chill, I open books, I watch the news, you know I’m like an old man, and I just get to it. I don’t think too much, there’s no fear, everything you make is amazing. But you could know if you need to push further or not. That’s where you need to be true to yourself as an artist because you can tell if you can actually make that painting better or not, so I always make all my paintings as if it’s my last ones because I understand the art of the time. I don’t joke with time, I feel like that’s one of the most important things in my process, the time at which I used to create and yes, some paintings take months, weeks, and years and I get back to it. And some, I finish right there.”

I don’t work on one painting, I work on four or five paintings at the same time and I have the same palette. And I don’t go to places to look for inspiration, I create my own inspiration. I enjoy collecting things that inspire me and stimulate my mind—furniture; figurines—then curating, arranging, and redesigning my studio. I’m like a mole, I live 35 minutes away and I’ve been in my studio for two weeks now, the only thing I do is Uber eats and just eat.

MÓYÒSÓRÉ MARTINS, MODACULTURE MAY 2024

“My wife and kids come to check on me. It’s also a blessing to have someone who understands your life, not trying to change you or trying to make you live like how they wanna live. I’m free and being free adds up to how I create. I’m free mentally and spiritually. I have no weight on me so instead of internalizing things, I pour everything on my canvas, and I have no pity for my canvas because I really treat them ‘ruggedly’ because I don’t want them to look very fine and pretty because I’m not fine and pretty because I’ve been through a lot, I’m scarred, it takes a lot.”

Martins is a man who is rough around the edges, as you can probably tell by now, and he is not afraid to let all of that show in his art. One could tell as the conversation starts to take an even deeper but not unexpected turn, and he leans into his vulnerability and bares his emotions.

“There are some things there’s no way I can heal from, I just need to carry the cross like that, and there are things I will forever be trying to heal till I leave this phase because I’m scarred forever and everything shows in my works, and how I treat people, and how I listen to people and understand them, and being emotionally intelligent, and being able to say ‘no’ and being able to say ‘yes’ and standing on your words, meeting objectives and stuff like ‘In a week, these are how many paintings I’m making, whether you sell or you don’t sell.’ You need to have a routine, you need to be structured. Most artists are not like that. They take it as a freestyle, you need to treat it like a 9-5, you need to clock in and clock out, and you need to clock in forever. That process sometimes is something I can’t explain because I really don’t understand how I make the painting. All I know is I have a routine, not really a process but timing; certain foods I need to eat, certain things I need to do. I’m always by myself, I like being alone a lot, by being alone I get to have the finest clarity I need without my thoughts being hindered or tinted by any source of external inspiration or whatever the case, not like trying to check the internet and looking for things. The structure is what makes you who you are and you can just tell, those things don’t lie, sometimes you might be a genius, but if you don’t have a routine or you are not structured, you can’t make anything useful of yourself. You might be having the best time of your life but when that time (for work) hits, it’s ‘Alright I got to go.’ Most artists don’t see that. And that’s what separates artists from artists,” he reveals as he demystifies the place of structure and discipline in an artist’s life, and the necessary pain of the process, one masking the other.

So what does it take to stand out as an artist? The painter emphasises structure, ethics, vision, and an unparalleled focus on the art. “I really don’t have many artist friends because they’re very competitive, everybody wants to be the best artist, they want to be number 1. As much as people don’t see it like that, it’s a very competitive sport. I want to be the best, the most sought-after, the most sold, but are you putting in the work? Do you have the ethics? Do you have the structure that’s gonna take you to where you’re going? That’s what separates the people out there from the people lamenting and complaining. That’s what I’ve been doing, routines and structures, being on my own, solitude and everything. Abstinence from things that are gonna take my superpower away, you need to know these things, it’s spiritual, it’s like music.”

A section of Móyòsóré Martins’s studio

Everything Móyòsóré Martins has done, everything he does now, and everything he plans to do in future leads him down one path: timelessness. For him, it’s about what his work says, and how it will be perceived in the long run. “Will it make them want to buy new furniture, or will it add to what they have going on?” At this point in the conversation, he’s starting to preach the essence of training oneself as an artist to better heights and improved taste.

An artist needs to have good taste in everything: fashion, food, seeing things and understanding the value, aesthetics, silhouettes, cut, design and everything because the people that collect your stuff are people of the finest quality of taste so why would they want to buy something that looks ‘raggedy’ and put in their living room or bedroom? So, the stuff needs to be amplifying, stimulating, something they could learn from, something inspiring, and something mind-blowing. I say mind blowing not culture-shocking because human beings don’t like that.

MÓYÒSÓRÉ MARTINS, MODACULTURE MAY 2024

“Culture shock is like change and we are not used to changing, we love things that are nostalgic, that we’ve seen before. As soon as we see something brand new, it’s a turnoff, that is how racism and everything started. People are scared of things they don’t know, so we need to create things that are welcoming. As much as your message could be deep, dark, and heavy, you should learn to figure out a way to express it in a comforting manner, if that makes sense. That’s why my paintings are dark, yet very childlike. Channelling those emotions, that’s what I have been doing, and I keep learning, trying to gain mastery and pushing myself to the next limit every day.”

And where does he see himself going, what kind of messages does he want to pass through his art as he continues to grow? “I see myself being happier, I see myself designing things that would implement the functionality of human beings, especially growing up in Nigeria, I saw things we lack and need that could make our lives better, things that we don’t even think of, like having a good bus stop and everything, public toilets—things that make us human—parks, and places you could go sit down and just chill without spending money because everything doesn’t have to do with currency,” he says excitedly talking about all the ways he intends to impact the lives of others and his legacy. “I want to have an organisation where I could help artists by giving them scholarships, make them find their true artistic self, that I would be doing next year.”

“And I’m enjoying the now, I try not to dwell too much on things like that, so I try to make use of the time I have now, and that’s what I’ve been doing and that’s how I see myself and that’s what I know for myself.”

He talks more about his intentions of becoming more humanitarian, changing the dynamics of daily human operations, and making his art more functional in society. “I feel most of the designs we have now aren’t complete, everything is being put out in a rush like a teaser, and everything that’s out now isn’t new. It could be better, it could be safer. Living in America, they don’t have public toilets. When I came to America, I always wanted to pee all the time, especially because it’s cold, your bladder gets filled up, and you always want to pee. I feel like a basic human being needs a public toilet. We’re animals, we need to go. There is no good bus stop in America. They all sit in the cold, the buses don’t come frequently, and you can’t have a normal job if you’re preparing to take a transportation system like that so I really want to go humanitarian and change the dynamics of how we operate as human beings.”

He’s also taking it back home to Lagos, Nigeria where he plans to design bus stops and transportation systems. “That’s something I really want to do as well when I come back home: inventing and designing new bus stops and transportation systems using simple designs that would really make our lives feel better, that would make you feel like oh! I got it. So I just want to be more humanitarian and implement my art and designs into things that would make our lives functional as human beings in general so that’s my goal—improving functionality, design, how we live, how we see spaces, the space, curation of space, the things you need, and the basic needs of human beings that make your lifestyle more suitable for you to live. Because I live here and live there and have the best of both worlds, I could tell the lack there and the lack here too in as much as everything looks so rosy. So, once you could figure out what they need, you could find the solution to it, and I feel like I’ll have the solution for it. It’s just that the time isn’t right, and I do believe when the time is right, everything will be like in reality.”

From New York, Móyòsóré Martins took a trip to Accra, Ghana where he is currently participating in a six-week residency with MOU Arms Around The Child foundation. He has his art studio set up with the children’s school from April through May 2024, volunteering to help the school and orphanage, creating art with the children.

Móyòsóré Martins during his residency at Arms Around the Child| Image courtesy of the artist

One of the works will be auctioned off in the fall in London at an exhibition, and part of the proceeds will go to the school orphanage.

Photographs by: Daniella Liguori© 2024